These Are Probably the People Who Will Build The First Starship

2013.10.27

A group of scientists, engineers, and scifi writers recently gathered at the Royal Astronomical Society to discuss ideas on how interstellar travel might happen.

A new Economist article points out that starship research is enjoying something of a boom now. A few years ago, there was only one organization working on the prospect of interstellar travel. Now there's at least five including DARPA, NASA and several private organizations.

The event took place on October 21 and was keynoted by Astronomer Royal, Lord Martin Rees, and featured talks by many including James and Gregory Benford, Stephen Baxter and Ian Crawford.

The organizers also compiled a Starship Century book, which included essays and fiction from the above speakers, but also Stephen Hawking, Freeman Dyson, Paul Davies, Robert Zubrin, David Brin, Neal Stephenson, Joe Haldeman and Nancy Kress.

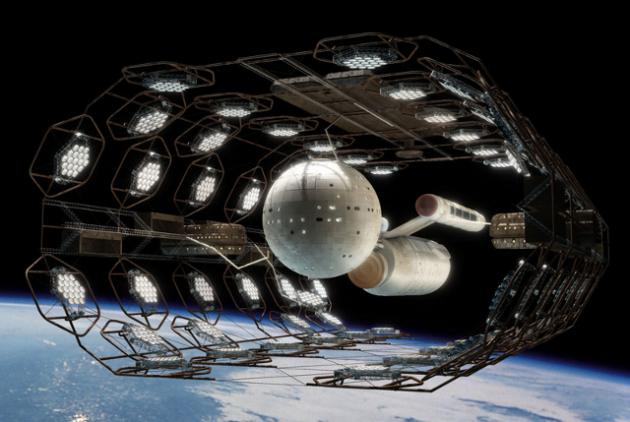

They discussed ideas from Freeman Dyson, of his nuclear explosion powered rockets (called Project Orion), and Daedalus, to an unmanned vessel conceived by the British Interplanetary Society that that would use a fusion rocket to attain 12% of the speed of light, allowing it to reach Barnard’s Star, which is six light-years away, in a mere 50 years.

The Economist highlighted some of the current projects and what needs to be overcome to make all of it happen:

The chief problem, as Adams noted, is distance. During the cold war America spent several years and much treasure (peaking in 1966 at 4.4% of government spending) to send two dozen astronauts to the Moon and back. But on astronomical scales, a trip to the Moon is nothing. If Earth—which is 12,742km, or 7,918 miles, across—were shrunk to the size of a sand grain and placed on the desk of The Economist’s science correspondent, the Moon would be a smaller sand grain about 3cm away. The sun would be a larger ball nearly 12 metres down the hall. And Alpha Centauri B would be around 3,200km distant, somewhere near Volgograd, in Russia.

Chemical rockets simply cannot generate enough energy to cross such distances in any sort of useful time. Voyager 1, a space probe launched in 1977 to study the outer solar system, has travelled farther from Earth than any other object ever built. A combination of chemical rocketry and gravitational kicks from the solar system’s planets have boosted its velocity to 17km a second. At that speed, it would (were it pointing in the right direction) take more than 75,000 years to reach Alpha Centauri.

Nuclear power can bring those numbers down. Dr Dyson’s bomb-propelled vessel would take about 130 years to make the trip, although with no ability to slow down at the other end (which more than doubles the energy needed) it would zip through the alien solar system in a matter of days. Daedalus, though quicker, would also zoom right past its target, collecting what data it could along the way. Icarus, its spiritual successor, would be able at least to slow down. Only Project Longshot, run by NASA and the American navy, envisages actually stopping on arrival and going into orbit around the star to be studied.

But nuclear rockets have problems of their own. For one thing, they tend to be big. Daedalus would weigh 54,000 tonnes, partly because it would have to carry all its fuel with it. That fuel itself has mass, and therefore requires yet more fuel to accelerate it, a problem which quickly spirals out of control. And the fuel in question, an isotope of helium called 3He, is not easy to get hold of. The Daedalus team assumed it could be mined from the atmosphere of Jupiter, by humans who had already spread through the solar system.

It is a very interesting article, and it goes in to depth of more tech that we may be using for future space travel. Read it all here.Chemical rockets simply cannot generate enough energy to cross such distances in any sort of useful time. Voyager 1, a space probe launched in 1977 to study the outer solar system, has travelled farther from Earth than any other object ever built. A combination of chemical rocketry and gravitational kicks from the solar system’s planets have boosted its velocity to 17km a second. At that speed, it would (were it pointing in the right direction) take more than 75,000 years to reach Alpha Centauri.

Nuclear power can bring those numbers down. Dr Dyson’s bomb-propelled vessel would take about 130 years to make the trip, although with no ability to slow down at the other end (which more than doubles the energy needed) it would zip through the alien solar system in a matter of days. Daedalus, though quicker, would also zoom right past its target, collecting what data it could along the way. Icarus, its spiritual successor, would be able at least to slow down. Only Project Longshot, run by NASA and the American navy, envisages actually stopping on arrival and going into orbit around the star to be studied.

But nuclear rockets have problems of their own. For one thing, they tend to be big. Daedalus would weigh 54,000 tonnes, partly because it would have to carry all its fuel with it. That fuel itself has mass, and therefore requires yet more fuel to accelerate it, a problem which quickly spirals out of control. And the fuel in question, an isotope of helium called 3He, is not easy to get hold of. The Daedalus team assumed it could be mined from the atmosphere of Jupiter, by humans who had already spread through the solar system.

Top image: Daedalus Class Starship as conceived by Sean Robertson.

More Articles

Copyright © Fooyoh.com All rights reserved.